Discipline and Compliance in “Reefer Madness”

A group of friends is having fun in an apartment. A guy comes out of the bedroom and sees another guy abusing a girl. They have a fight. Someone accidentally kills the girl. One of the guys thinks that he killed the girl. He can’t tell if that’s true because he smoked a joint earlier. Does this sound like a scene taken from everyday life? If not, that’s probably because it’s a scene from Reefer Madness, a 1936 propaganda movie dealing with the social anxiety over marijuana in the 1930s US.

Immigrants: the Source of All Evil

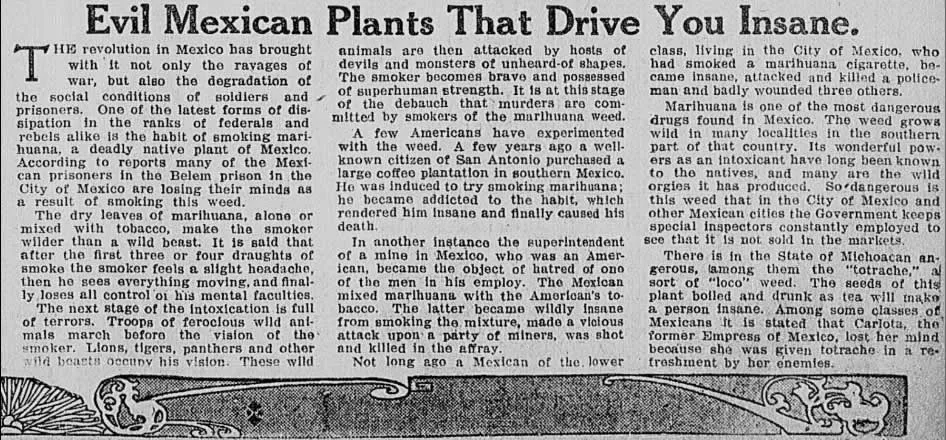

Reefer Madness (originally made as Tell Your Children and sometimes titled as The Burning Question, Dope Addict, Doped Youth, and Love Madness) captured perfectly the essence of the anti-marijuana campaign that was initiated by Harry J. Anslinger. Anslinger was a government official, who served as the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and remained its head for three consecutive decades. His flagrant propaganda included racist accusations linking marijuana to black communities and Mexican immigrants. From 1910, there was a significant increase in Mexican migrants in the U.S. due to the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. According to the Library of Congress, between 1910 and 1930, the number of Mexican immigrants counted by the U.S. census tripled from 200,000 to 600,000, with the actual number being probably far greater.

Immigrants served as a scapegoat for the U.S. media, which claimed that there was a causal relationship between the use of cannabis for recreational purposes among the immigrant community and the crimes committed in the U.S. Immigrants were portrayed as violent criminals, posing a threat to the American way of life. This perception laid the foundations for the social construction of cannabis as one of the most dangerous drugs. By 1931, 29 States had outlawed marijuana, with the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act putting a definitive end to the legal use of Marijuana. The Tax Act implemented a host of taxes, restrictions, and regulations making it almost impossible to purchase or sell cannabis in practice.

Newspaper article from The Tennessean that reflects the anti-marihuana(sic) propaganda. 1913 (photo: newspapers.com).

Great Versus Lost

Reefer Madness could be easily summarized in the sentence: beware! Your children will descend into madness if they smoke marijuana (and possibly commit suicide at some point). The film can be seen under the constant contrast between the Great Generation (born in the 1900s-1920s) and the Lost Generation (born between 1883 and 1900). The generation gap becomes apparent through the ideally portrayed Lost Generation and the deviant Great generation. Parents, teachers, principals, judges, attorneys are given the most screen time via lengthy monologues to establish their authority and strictly set the moral standards that young people must adhere to. The deviation from those standards ―as in smoking marijuana― can and will result in exemplary punishment.

Young people, on the other side, seem unable ―and somehow reluctant― to defend themselves from the punitive authority. They seem to lack critical thinking skills, as they are susceptible to any “harmful” influence and unable to protect themselves. Further to their impersonal character, young people are depicted as a homogeneous mass consisting of relatively indifferent and easily manipulated personalities. Contrary to the bodies in power, young people engage only in short dialogues, they don’t elaborate on any issues, and are not concerned about anything else except for having a good time.

One of the movie characters (Ralph) is arrested for murder (photo: commons.wikimedia.org).

While the audience’s engagement with the characters could potentially make the anti-marijuana message more effective, there seems to be little attempt to make the characters relatable to younger audiences. Firstly, the names chosen for the characters (Mary, Bill, Mae, Jack, Ralph, Jimmie) combined with their flat personalities and the lack of distinctiveness make it difficult to even remember who is who and to follow a character from the beginning to the end. The difficulty in identifying the different characters could be partly due to the over-saturated plot, but it is also an indicator of the intent to mainly show the power mechanisms that certain people have the right to use in the name of protection and justice. Therefore, the aim is not actually to protect people from the “deadliest drug” but to consolidate power through the viewing experience.

More Than a Cult Classic?

Even though the initial purpose of the movie was to warn parents of the deadly consequences of marijuana consumption, Reefer Madness ended up serving different purposes. Besides being a cult classic and one of the most popular examples of midnight movies, Reefer Madness was used as a movie-counterexample to advocate the… legalization of marijuana in the United States by Keith Stroup. Keith Stroup was the founder of The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, one of the oldest activist organizations dedicated to ending marijuana prohibition in the States. As part of his fund-raising campaign to legalize marijuana in the States, he started screening the film, a copy of which he purchased for $297, in colleges and campuses.

Claiming little artistic merit for its story and technical aspects, Reefer Madness along with several other drug exploitation films of that period (Assassin of Youth, Marihuana, Narcotic, The Pace That Kills), remains a reminder of the different readings a movie can have depending on its context.

[imdb id=“tt0028346”]